Practice like you care — but not like your worth depends on it.

4-minute read

You roll out your mat and say: I need to work hard today to earn my… weekend/dinner/ gin and tonic…

Practice and non-attachment: Abhyāsa and Vairāgya. This pairing of effort and letting go echoes what my teacher, psychologist and meditation teacher, Tara Brach often points to, that healing doesn’t come from striving to become someone else, but from meeting ourselves with clarity and care.

Where do the Yoga Sūtras come from?

The Yoga Sūtras are a foundational text of classical yoga philosophy, traditionally attributed to Patañjali, and dated to the early centuries of the Common Era (roughly 200 BCE–400 CE). The text is composed of 196 short aphorisms, or sūtras—a Sanskrit word meaning “thread.” Each sūtra is deliberately concise, intended to be unpacked through study, reflection, and practice rather than read as a set of rules.

The Yoga Sūtras outline a framework for understanding:

the nature of the mind,

why humans suffer,

and how practice can reduce suffering and support clarity, steadiness, and freedom.

Although the text emerged in a very different cultural and historical context, its focus on attention, habit, perception, and emotional reactivity makes it surprisingly relevant to modern psychology and wellbeing.

Yoga philosophy and suffering: a shared starting point

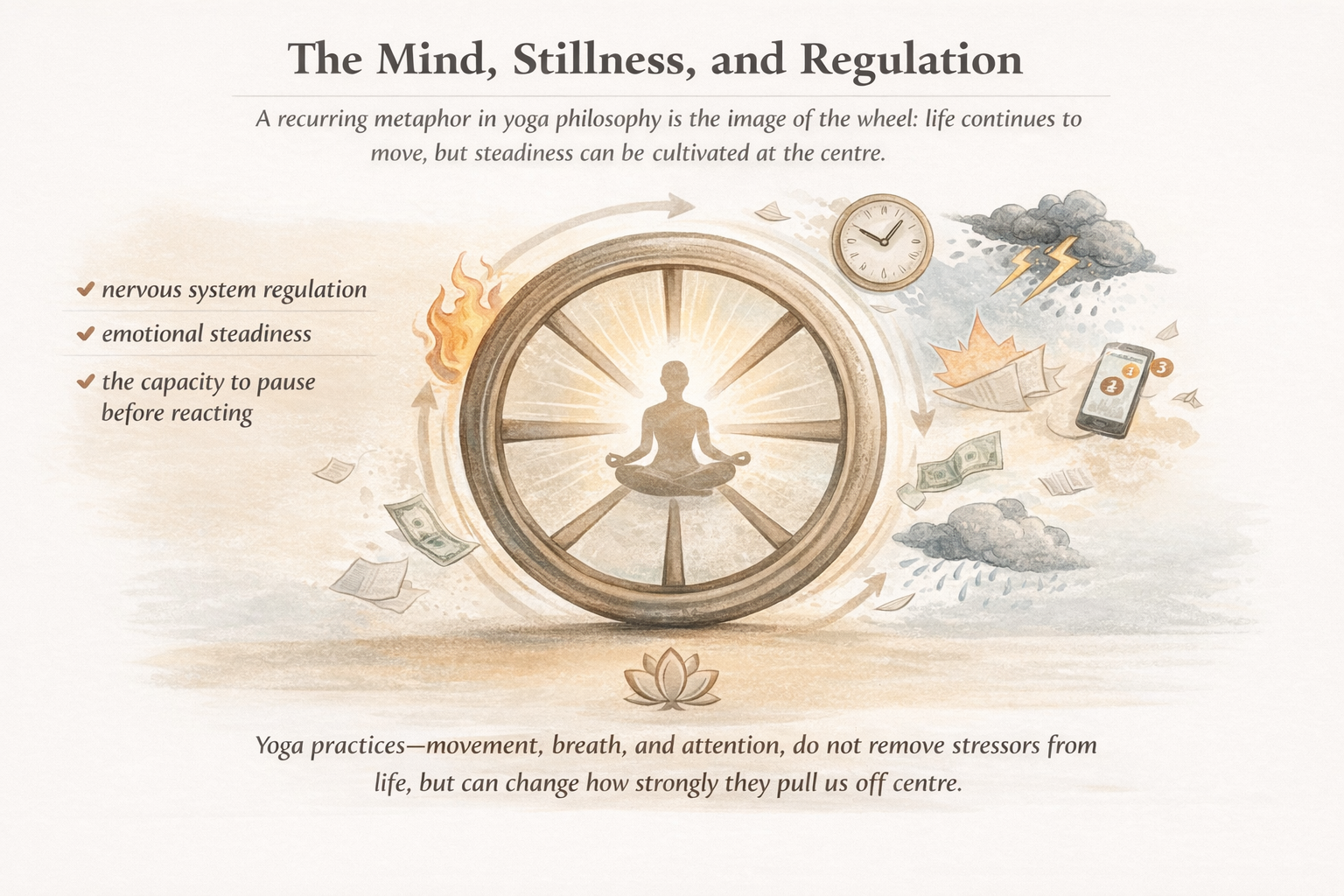

A central assumption in the Yoga Sūtras—shared with many Eastern philosophical traditions—is that life involves suffering (duḥkha). Difficulty, discomfort, and uncertainty are not seen as failures or anomalies, but as part of being human.

From a psychological perspective, this aligns with a simple but powerful idea:

Distress often comes not only from what happens to us, but from how we interpret and react to it.

Modern psychology describes this in terms of cognitive appraisal, emotional regulation, and stress response. Yoga philosophy approaches the same territory through a different lens, focusing on how mental habits (vṛttis) shape experience.

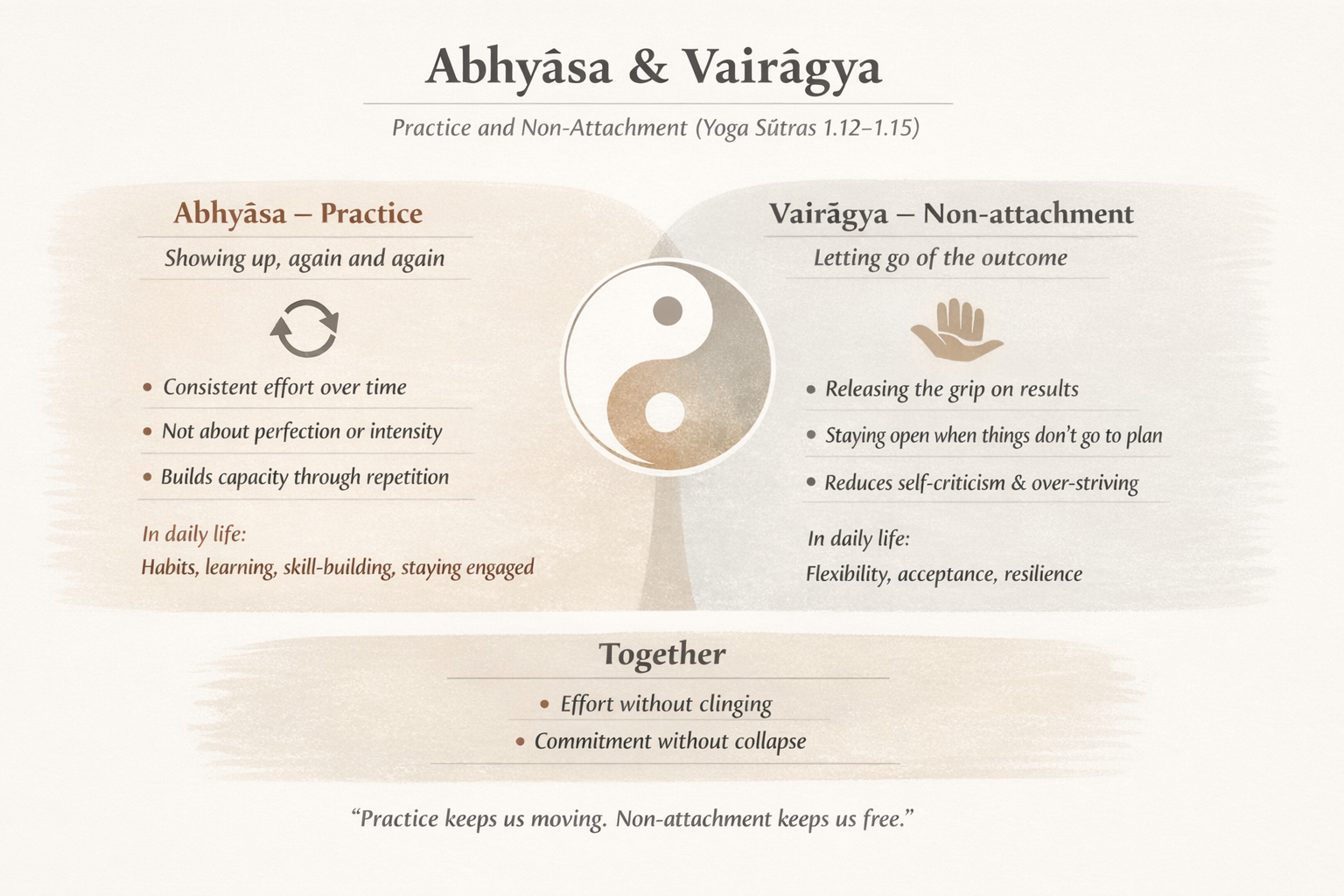

Abhyāsa and Vairāgya: practice and non-attachment

(Yoga Sūtras 1.12–1.15)

One of the most practically useful teachings in the Yoga Sūtras is the pairing of abhyāsa and vairāgya.

Why these two are taught together

Abhyāsa without vairāgya can lead to:

burnout,

injury,

rigidity,

identity becoming tied to performance.

Vairāgya without abhyāsa can lead to:

disengagement,

lack of direction,

avoidance.

Together, they form a middle path,what psychology might describe as committed action with flexibility. Teachers can explicitly name this balance for students, helping them understand that yoga practice is not about “doing more,” but about refining attention, effort, and response.

AND ofocuse all of this with: Ahimsa, compassion as a practical skill! (Yoga Sūtras 2.30–2.35)

Ahimsa, the first of the yamas (ethical principles governing how we relate to the world), is commonly translated as non-violence. In practice, it is better understood as active compassion, expressed through thought, speech, and action.

In the Yoga Sūtras, ahimsa is not framed as moral perfection, but as a discipline that reduces harm,internally and externally.

Psychological cross-reference: self-compassion

Modern psychology, particularly the work of Kristin Neff, describes self-compassion as treating oneself with the same care and understanding offered to a close friend. Research shows that self-compassion supports:

emotional regulation,

resilience,

reduced shame and self-criticism.

Yoga philosophy reaches a similar conclusion: when internal aggression softens, external aggression tends to soften as well.

Boundaries are part of non-violence

An important clarification,especially relevant in modern teaching contexts,is that ahimsa does not mean endless self-sacrifice.

Both yoga philosophy and psychology recognise that:

lack of boundaries leads to resentment and burnout,

sustainable care for others requires care for oneself.

In teaching terms, this supports clear cueing around rest, choice, and autonomy, and challenges the idea that pushing through pain or exhaustion is inherently virtuous.