Yoga’s “Hidden” History: What Modern Teachers Need to Know (and Unlearn)

4- minute read

If you trained as a yoga teacher in the West, you were probably given a familiar storyline: an ancient lineage, a handful of key texts, and a handful of modern teachers who “brought yoga to the West.” It’s a tidy narrative, easy to teach, easy to repeat, easy to package into a weekend module.

It’s also incomplete.

Why do yoga teachers feel compelled to teach history at all?

Why do we spend time on long, philosophically dense histories of yoga when, day to day, we’re teaching bodies?

In most movement disciplines, history is optional. A running coach isn’t expected to teach the cultural story of road racing before helping you improve your stride. A Pilates teacher might nod to Joseph Pilates, but rarely walks students through the evolution of anatomy, dissection, and physiology.

Yoga is different. Many of us feel a responsibility to reference roots, lineage, and tradition, partly out of respect, partly to avoid appropriation, and partly because “ancient wisdom” lends authority. It signals depth. It reassures students (and sometimes teachers) that what’s happening on the mat is more than exercise.

But here’s where it gets tricky.

Modern yoga spaces, especially in the West often teach predominantly female-presenting, often white, often middle-class students. These are not the primary audiences many ancient yogic texts were written for, and they are not living the conditions those traditions assumed. When we lift quotes, concepts, or stories from ancient sources and drop them into a contemporary studio, it can create a subtle mismatch: what we feel we should say versus what our students actually need.

My point isn’t “stop teaching history.” It’s: teach it better.

Not as romance. Not as proof of legitimacy. Not as a decorative background story to make a class feel profound. Teach it in a way that supports the realities of modern teaching, real bodies, real nervous systems, real lives.

The biggest thing missing from teacher-training history modules: nuance

Most teacher trainings offer a straight-line version of yoga history that looks something like:

· Vedas → Upaniṣads → Yoga Sūtras

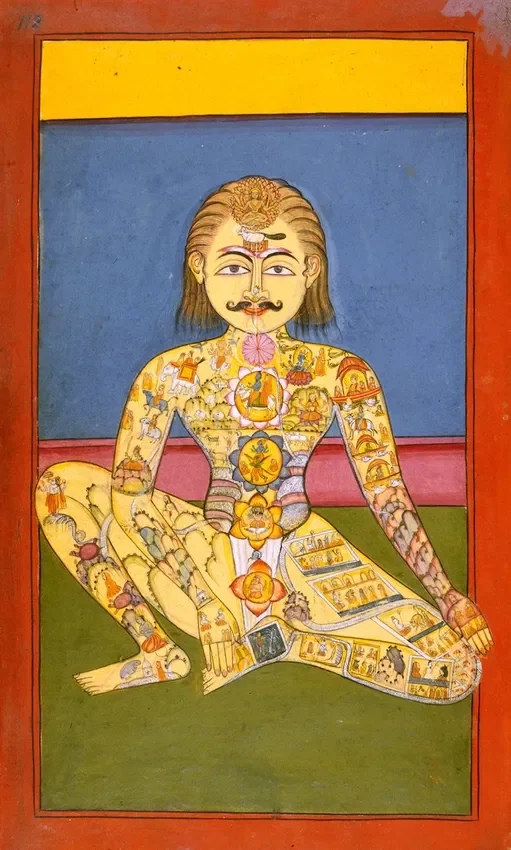

· a brief stop at subtle body theory

· a nod to “when āsana began”

· then: yoga goes West, gets commercialised, and cultural appropriation becomes the cautionary ending

Let's not dismiss this structure entirely.

A simplified narrative can be a useful scaffold, something to hold onto when the field feels overwhelming. The issue is that it’s often taught as the story rather than a story.

Real history is never a straight line. It’s contested, regional, political, multilingual, and messy. There are alternative lineages and interpretations, different motivations, and different communities shaping what yoga means in different places and times. When those complexities are stripped out, we end up with a yoga history that is neat enough to teach in a short module, but too tidy to be true.

While yoga itself is ancient, the academic study of yoga history (particularly in Western institutions) is relatively young. That means many widely repeated “facts” are inherited narratives, passed from teacher to teacher, rather than carefully sourced scholarship.

So if your yoga history module felt overly tidy, it probably was.

The invitation here is not to become a historian overnight, but to adopt a more mature posture as a teacher: to treat what you were taught as a starting point, not a final authority.

“Sanskrit is the language of yoga” (…is a simplification)

A claim that is repeated constantly in modern yoga education: that Sanskrit is the language of yoga.

Many modern posture names were “Sanskritized” after the fact, particularly as yoga was packaged, formalised, and marketed. In other words, the Sanskrit label is sometimes added after the movement exists, rather than being evidence of ancient origin.

Yoga has lived through multiple languages and communities, including vernacular traditions and forms like poetry that rarely make it into mainstream teacher training. When we narrow yoga’s legitimacy to Sanskrit pronunciation, we risk turning language into a performance of authenticity rather than a meaningful connection to context.

And if we reduce “respect for yoga” to whether someone can say vīrabhadrāsana correctly, we may miss far bigger ethical questions: who is being served, what is being claimed, what is being borrowed, and what is being understood.

In that sense, I’m not suggesting to “stop using Sanskrit.” I suggest: understand what Sanskrit is doing in your teaching. Is it clarifying? Is it connecting students to something real? Or is it standing in for depth you haven’t had the time, access, or training to build yet?

That’s not a criticism. It’s a practice of honesty.

A closing thought. You can be respectful without being performative. You can be rooted without pretending certainty. You can honour yoga’s complexity without turning your classes into mythology or your teacher identity into a history project.

And perhaps most importantly: you can teach what you actually know, in language that actually serves the people in front of you while staying curious enough to keep learning.

This, is me, this is why my teaching keeps evolving, as I do, through practice and study across different genres. IStay Curious!

References

Mallinson, J. (2012). Śāktism and Haṭha Yoga. Demonstrates plurality of yogic traditions and textual practices.

Singleton, M. (2019). The Ancient Roots of Modern Yoga? (Article). Challenges assumptions of antiquity in posture-based yoga.